"Doc" Clutz of Mercersburg

Dr. Paul and Catherine Clutz in the courtyard of their home at 29 N. Main St., Mercersburg, ca. 1972

Paul Alexander Clutz, M.D. - "Doc Clutz" to many-was a medical doctor in Mercersburg for half a century - from 1933 to 1983. The Mercersburg Journal noted his arrival: Friday, September 8, 1933 Dr. Paul A. Clutz has opened a physician's office on West Seminary Street, Mercersburg.

He had come from Gettysburg with his wife Catherine ("Cotty") and their two little boys - Henry, age 2, and William, just 6 months old.

Starting a practice in a new town during the Depression would prove to be a daunting task. Acquiring new patients took time. Those he got often had little money to pay. Catherine often had to try to make a meal for the family improvising with meat, vegetables and fruit that patients gave to Dr. Clutz in lieu of cash. Her father, Doctor Harry Hartman of Gettysburg, would often visit, he and his wife Lizzie would load up the car with meats and produce from Adams County to fill the Clutz pantry. Over the next 29 years, they would exchange Sunday visits, bringing each other various and sundry foods, furnishings, etc. Pop always referred to this as "The International Trade".

Paul had moved away from Gettysburg to avoid practicing medicine in the same town as his father- in- law. He and Catherine chose Mercersburg because they wanted their boys to enjoy the fine secondary education at the Academy. It was a wise choice. We received an excellent education from the dedicated women and men who taught in the Mercersburg schools, and later had the benefit of the broader curriculum available at the Academy. We had the good fortune to live at home as Day Students, maintaining the friendships with our neighbors, while gaining new friends at the Academy.

The Lincoln Highway, U.S. 30, provided a good road to support "The International Trade" between Mercersburg and Gettysburg. In the early years, parental visits from Gettysburg were invaluable to Catherine as her busy husband built his practice. In later years, her trips back to Gettysburg gave support to her parents when they needed it. Some of those trips were harrowing, especially during WWII, as when she had drive home with her three young boys from a Gettysburg visit, in a snowstorm, up the slippery slopes of South Mountain.

Dr. Clutz first rented a three-story house on West Seminary. His office was on the first floor, with his family living upstairs. But after five years, Paul and Catherine purchased the historic stone house at 29 North Main. It had been built in 1790 by Elliot Lane (who later moved nearer to the square to what would become the Harriet Lane House). The house had been home of the Richey family for at least 50 years, and for the next 55 years would be home to the Clutz family. Mrs. Richey in 1900 had built a brick addition in the back, with a balcony that overlooked her extensive gardens. The house abutted the two-family home of the Steiger Brothers, Seth and Lynn, and its property extended behind the Steigers' to the alley and The Hitching Yard. Across a narrow walkway to the south were the homes of Mayor Stroup (later the home of Seth and Mary Metcalfe) and the Rev. J. G. Rose, whose daughter Virginia was the town telephone operator. Across North Main Street was the home of Jack McLaughlin, the owner of McLaughlin's Drug Store (up the street at the James Buchanan Hotel); the home ofretired County School Superintendent John Finafrock and his wife Mary was just to the south, and the homes of Fan Rhea and John Karper with his broom shop were just to the north by the alley.

The spacious house was adapted to accommodate the doctor's office and , I treatment room on the fust floor, with the entry hall serving as waiting room. A large porch of limestone surrounded the house, with steps to the porch and main door, which became the office door. The family entrance was at its end on the side of the house, that had previously been the door to Mrs. Richey's dining room. After WWII, the porch was removed and the house remodeled to create a suite of offices and treatment rooms with its own "Doctor's Office" entry on the south side, and the original house entry, living and dining rooms restored to the front first floor. But for many years, on occasion we would still come downstairs into the hall to find someone sitting there patiently waiting for the doctor.

The spacious house was adapted to accommodate the doctor's office and , I treatment room on the fust floor, with the entry hall serving as waiting room. A large porch of limestone surrounded the house, with steps to the porch and main door, which became the office door. The family entrance was at its end on the side of the house, that had previously been the door to Mrs. Richey's dining room. After WWII, the porch was removed and the house remodeled to create a suite of offices and treatment rooms with its own "Doctor's Office" entry on the south side, and the original house entry, living and dining rooms restored to the front first floor. But for many years, on occasion we would still come downstairs into the hall to find someone sitting there patiently waiting for the doctor.

Pop was busy with his practice, but he still found time for his hobbies. He was a superb photographer, and had his own darkroom built off the second floor rear bedroom. His collection of images of the hardworking citizens of the area, along with landscape images of the many stone arch bridges (most of which are now long-gone) that graced our roads in the early 20th century, captured the beauty of Mercersburg and its scenic surroundings. He was also an avid model railroader, with many evening hours in those days before television spent smoking his pipe while building tracks, rolling stock, and scenery for his train layout in the room outside his darkroom. It was a pre-TV version of a man-cave.

Then came World War Two. Just three years after moving into the house on North Main, he foresaw that America would soon be drawn into the war raging in Europe. So in April 1941, Dr. Paul Clutz enlisted in the Navy Medical Corps, seven months before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor led the government to officially declare war. He had previously been an Army Reserve Artillery Officer for 8 years. So instead of assigning him to be a ship's doctor, the Navy assigned the ex-Army officer to the Marine Corps. Thus in May, Paul left Catherine and his three little boys to go off to Camp Lejeune and Parris Island for amphibious combat training with the Marines. In August Catherine left the two older boys with her parents in Gettysburg, and took David with her to visit Paul in South Carolina. That brief time together would be their last for the next two years.

Then came World War Two. Just three years after moving into the house on North Main, he foresaw that America would soon be drawn into the war raging in Europe. So in April 1941, Dr. Paul Clutz enlisted in the Navy Medical Corps, seven months before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor led the government to officially declare war. He had previously been an Army Reserve Artillery Officer for 8 years. So instead of assigning him to be a ship's doctor, the Navy assigned the ex-Army officer to the Marine Corps. Thus in May, Paul left Catherine and his three little boys to go off to Camp Lejeune and Parris Island for amphibious combat training with the Marines. In August Catherine left the two older boys with her parents in Gettysburg, and took David with her to visit Paul in South Carolina. That brief time together would be their last for the next two years.

Catherine spent those years helping with the Red Cross at home in Mercersburg, then, when the old coal furnace went out during the winter of 1942, moved with the boys to an apartment in downtown Gettysburg to tend to her ill mother. Paul spent those years with the First Marine Division in the South Pacific, with them as they made the first landing at Guadalcanal. Knowing his artillery expertise, the Marines had him moonlight as a forward artillery observer to help fend off the desperate Japanese attacks on the Marine beach head. Malaria was a deadly opponent in the jungles of Guadalcanal. Paul was not immune. He would deal marlaria's symptoms through the rest of his life. It was the only thing that later could sometimes keep him from holding his normal office hours and making his daily house calls.

In 1944 he was reassigned back to the States to work at the Philadelphia Naval Hospital. Catherine and the boys joined him there. For the next twelve months they were a typical suburban couple, enjoying an active social life with the families of his fellow Navy medical officers. In August 1945, personal tragedy struck the family. Catherine gave birth to her fourth son. They named him Paul Edward Clutz. In those days the deadly complications of a birth of a child with a different blood type from the mother were little understood. David, born with the same potentially deadly difference from his mother, had survived. Paul Edward was not so fortunate. They mourned the loss of their infant, and buried him in the family plot in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery.

In early 1945, Lt. Cdr. Clutz was ordered to Pearl Harbor on a difficult management and diplomatic mission. He was ordered to shut down a home-brew penicillin manufacturing operation that was the darling of the Oahu Junior League. Those society women had been recruited by his predecessor to collect bandages and coffee cans. In a shed lined with shelves, the penicillin fungus was grown in a water solution in the cans, with the bandages allowed to soak in the mixture. These were shipped off to the battlefront aide stations, but the weak concentration of penicillin in the bandages was minimally effective at stopping infections. By 1945, real pharmaceutical companies were making vials of high strength penicillin for use with hypodermic syringes, making the Hawaiian home-brew bandages obsolete. Lt. Cdr. Clutz quickly shut down the operation, as ordered, but at the cost of the ill-will of the Junior League ladies who'd been deprived of their self-important "contribution to the winning of the war" in the Pacific. He would not have been invited to their victory parties!

By summer of 1945, Catherine and the boys were back at home in Mercersburg, cheering in the impromptu parades of horn-blowing vehicles around the fountain in the square - first to celebrate V-E Day, and in August, V-J Day, happy and relieved at the ending of the war-the soldiers would soon be home!

Newly promoted Commander Clutz hung up his Navy uniform and returned to the trousers, shirt, bowtie and tweed jackets he felt comfortable in. Paul was back to being Mercersburg's "Doc Clutz". The question was, would he stay there? He had made quite a reputation among his fellow physicians in Harrisburg and Chambersburg for his diagnostic skills, correctly identifying the causes of mysterious illnesses in patients he sent to them for specialist care. Several doctors urged him to take his boards in Internal Medicine and move to Chambersburg. Practicing in that larger community certainly tempted him. He had been born there, and lived on Montgomery A venue as a boy when his father was the city engineer. He had staff privileges already at the Chambersburg Hospital, and would have fit comfortably into the local medical fraternity.

Fortunately for us boys ( if not for Catherine - she saw it as a return to a suburban life like they had recently enjoyed in Philadelphia), he decided to pass up that opportunity. He stayed in Mercersburg. He'd come to know the local residents, town and rural, and liked his patients. He liked the control he had over the pace of his practice. He liked the challenging variety of the medical problems he faced. To just focus on internal medicine would be boring, compared to his practice in a rural town where his office was the local emergency room, and where he had to ride off in the middle of the night to deliver a baby to a farm wife off in the Little Cove, for example. Admittedly, that took its toll, he was essentially on call 24/7, whereas the Chambersburg practice would have allowed him (and his wife) a normal workday life.

Fortunately for him, Cotty didn't object too strenuously. She would have loved living in the larger community in some ways, with its many amenities not available in a small town. But she was the daughter of another small town doctor who also was on-call 24/7, often driving out into the country at night to deliver a baby (Doc Hartman eventually delivered 5000 in Adams County!). She knew how her father thrived on that, and could see her husband in many ways was cast in the same mold. And so she, as always, supported him in his decision to stay, just as she had when he moved her 40 miles away from her beloved Gettysburg to this small town at the foot of the mountains.

Life in a small town was not what Mother had expected for herself when she graduated from college - Barnard College of Columbia University in Manhattan. Her parents had sent her on "the Grand Tour" of Europe as a graduation present. Two months of immersion in the classic art and architecture, marvelous scenic vistas, the varied cuisine of Europe and even North Africa enhanced her appreciation for cultural stimulation. Such might also be found back home in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, but would indeed be rare in small Pennsylvania towns. Fortunately for Catherine, Mercersburg was one rare town that did include samplings of that culture, because of the Academy and its faculty. She formed friendships with her neighbors and with wives of faculty members. Catherine was a fine pianist, as was Cecil Lefevre, who lived across Main St. Mrs. Hartman had given her a baby grand piano, and Cecil often came over to join with her to entertain family and friends with their bouncy renditions of Gershwin and Cole Porter tunes. Catherine was very active in the Women's Club, and especially so in the early 60's when the town library was moved to the historic Parker House - the stone building across from the Buchanan Hotel. Paul was a voracious reader, as was Cotty, so the wide range of literature available at Fendrick Library was of great value to them, especially in their later years.

In the early 40's, Charles Tippetts became Headmaster at the Academy. "Cotty" soon became close friends with his daughter Kitty Belle, who had similar academic background and interests in art, architecture, history, and a desire to see the world. This was strengthened when their next door neighbor, Tom Steiger, married Kitty. When Paul was away in WWII, Tom also enlisted as a Navy officer. One of Paul's fondest experiences in the South Pacific was when he was able to meet up with his fellow Naval Officer from Mercersburg. Kitty had become an officer in the Women's Army Corps, with tours overseas and in North Africa. After the war, Tom returned to town to begin his law practice. From then on, the two couples were the closest of friends, friendship that meant much to Paul, but which was invaluable to Cotty.

From the beginning of Paul's practice, Catherine assisted him in many ways - insuring the offices were kept clean, insuring that his scalpels and instruments were kept clean and sterilized, answering the phone when he was out making calls, all while raising three active little boys. To manage her workload, she hired a series of young women to help her. Often they were teenagers, willing to work, eager to learn all that "Mrs. Clutz" could teach them, to become more polished and aware of the ways of the wider world. This was before the age of television, when only books and movies brought a glimpse of life beyond the daily activity of their community for many of these girls. Some of them became close friends long after they had moved on from the Clutz household. Bernice Richesson started helping "Mrs. Clutz" at the house on West Seminary when she was just 15. In the years after WWII, now Mrs. Eugene Lowans, Bernice came back to help "Mrs. Clutz" a few days a week at the house on North Main. And, God bless her, after Catherine's death she took care of the house for Paul, made sure he had food (he never really learned to cook for himself, being married to a superb cook like his Cotty!), and in general did her best to help him to manage independently in the house as long as his health permitted.

Catherine had first met Paul when they were young, not yet teenagers. Doctor Hartman had rented a house for the summer on the northwest edge of Gettysburg by the college, where it was much cooler than at their home downtown on Baltimore Street. Paul's father Frank had just accepted a position as Professor of Engineering at Gettysburg College. He had his PhD in Astrophysics, but had never learned to drive, so he needed a home by the campus. Sara Clutz decided the place Dr. Hartman was renting was ideal, but went there to get a better look inside to be sure the house would also be suitable for her antiques business. She took Paul with her. Young Catherine found herself a bit intimidated by the no-nonsense red-headed businesswoman, but found herself liking her nice-looking, if quiet, son. They reconnected as teenagers. Paul invited Cotty to a school dance, and soon the two fell in love.

Paul had quite an independent streak. At age 17, he quietly left home, without announcing his plans, and headed for Philadelphia, where he signed on as an ordinary seaman on an oil tanker bound for Los Angeles via the Panama Canal. One can only imagine the consternation of his parents! In those days before radar, a forward lookout was an essential safety feature for a ship in such well-traveled waters. Paul was blessed with superb vision, and became the eyes of the ship, high up the mast, scanning the horizon for possible hazards. Some years later that same devilmay- care adventuresome spirit led Paul to talk Cotty into eloping. She was in college in New York, he was in medical school in Philadelphia. One February day he took the train to New York. She met him at Penn Station. They went down to City Hall, got a marriage license, and tied the knot at "The Little Church Around the Corner" on East 29th in Manhattan. Their union was kept secret from family and friends for nearly a year, while he finished medical school and she took off for her two month grand tour of Europe. Soon she was pregnant, her first-born Henry delivered by her father in Gettysburg. A year and a half later, William was born. She lived in Gettysburg with the boys while Paul did his internship at the Harrisburg Hospital. The wild adventuresome times were over, as the young couple moved to start their new life in Mercersburg.

Paul's thirst for adventure must still have been strong, when he made the decision to leave his medical practice, his wife and young boys to go off to join the Navy with the Marine Corps in mind, in those early months of 1941. He was 33 years old, with a family. He surely could have sat out the war in the quiet safety of Mercersburg. But his sense of patriotism would not allow him to shirk duty to his country in its time of need. He certainly got his fill of"adventure'', thrown into the midst of the heavy fighting on Guadalcanal a year later. He always looked back on his time in the Navy with the First Marine Division with pride. But I think those wartime years had slaked his thirst for that kind of adventure for good. Back home in 1945, he turned his energy into making himself a medical facility well equipped to provide all the latest techniques for diagnosing and treating his patients.

Paul's father Frank was an engineer-he'd earned his PhD in Astrophysics at Johns Hopkins in the 1890's. So was Paul's brother John. Clearly there was a strong genetic family disposition to embrace science and technology. Paul loved the practice of medicine, but he also loved the new medical technology available post-war. He built his new suite of offices at 29 N. Main to support his desire for independence. His bent for technology let him become proficient in using and maintaining the comprehensive suite of devices that would make his practice virtually selfsufficient. He wouldn't have to send patients off to Chambersburg or Hagerstown for the most basic testing procedures before he could treat them.

What used to be the kitchen was sub-divided into an X-Ray room, a diathermy and electrocardiogram room, and a darkroom for developing the xray plates as soon as he took them. The dining room was remodeled into an examination and treatment room, equipped with a modem examination table, a centrifuge for doing blood work, a refrigerator for vials of penicillin and other perishable drugs. What had been the dining room pantry became the storage room for medical supplies, and for the autoclave that Cotty used to sterilize his stainless steel instruments.

When the 194 7 renovations were complete, and the new equipment in place, his office was as capable as a hospital emergency room for most of the medical emergencies that arise in a farming community. Broken bones could be xrayed and set when the patient came into the office, avoiding trips to the hospital. Chest pains could be determined to be heartburn or heart attack by use of his electrocardiogram. Injured muscles could be treated right there with the diathermy. Wounds could be stitched up and bandaged right there. Blood samples could be drawn and tested while the patient waited. Mercersburg didn't yet have an ambulance service. So if the patient required hospitalization, Catherine, or Paul himself if the urgency demanded it, would load the patient into his car and drive them to the hospital.

The renovations to the property in 1947 went beyond the office. The barn by the alley was tom down, goodby was said to Mrs. Richey's garden, and a driveway was put in to access the garage that was built onto the back of the house. When a call came during the night to deal with an emergency at a patient's home, Doc would be able to hop out of bed in his back room over the office, go down the back stairs to get his medical bag, go into the garage to his car, and drive off to meet the patient, all without disturbing the rest of the family sleeping in the front of the house.

He also had a new oil furnace installed to replace the ancient coal furnace that had given his wife such grief during his wartime absence. With the new heating system, radiant heat pipes were embedded in the concrete floor of the offices, making the floor warm and inviting for kids to play on when they came into the examination room, and to make older patients warm and comfortable when they had to disrobe for examination or treatment.

The new suite of offices had their own separate entryway at the street on the south side, leading into a waiting room. Catherine had it comfortably furnished and decorated the walls with original art work. From the waiting room, a patient entered the business office for initial consultation. They went from there into the appropriate treatment room. When done, patients left through a side door to the passageway leading to the street.

When the offices were finished, and the family installed in the front rooms of the 1790 house plus the second floor of Mrs. Richey's brick addition, Paul and Catherine were pleased with the results - a comfortable home for the family with a modern, fully equipped office beside. But Catherine had paid a price for the renovations.

When the cellar under Mrs. Richey's addition was being dug out to put in a concrete floor, the workmen neglected to block off the kitchen stairway to the cellar. For the last nine years Catherine had been used to going down the first step or two to retrieve ajar of her home-canned fruit or jelly from the shelves at the side of the stairway. On that fateful evening in 194 7 she opened the door and stepped into the dark stairway. But the stairs had been removed just hours before, with no safety rail to block entry. She fell feet first down into the dirt-floored basement, landing on a pick - fortunately lying on its side. The fall broke her ankle, virtually shattering the bones. Surgery allowed her use of the ankle after some months of being confined to an upstairs bedroom. But the floating fragments would cause her spells of pain for the rest of her life.

The family eventually got back to normal - the boys in school, Catherine back on her feet. Paul had of course not interrupted his medical practice during her recuperation. Doc Clutz's routine had a basic structure of office hours in morning, afternoon, and evening with time in between for making house calls. In between patients he made meticulous notes on each case and carefully filed them. That basic structure was often honored in the breach, as emergencies arose, or a house call took longer than anticipated. Fortunately most baby deliveries seem to come during the night, so while it may have robbed him of sleep, it had minimal impact on the day's appointments. But medical conditions are not always respectful of neat time slots, and he would not be bound to a rigid schedule if it interfered with proper treatment of that condition.

Catherine's scheduled meals were often the victim of an afternoon house call that went too long, or were disrupted by an emergency phone call at dinner time. Her husband would leave the table to go deal with the emergency. And once again his plate would go back in the oven to be kept warm until he was able to return to finish his meal. Perhaps because of his time with the Marines amid a war, or just because his practice's frequent interruptions had made him that way, he wasn't bothered by eating cold or tepid food on these occasions. It bothered Catherine more than Paul. She was a good cook, and had put effort into making the family a nice dinner, and then by the time he was actually able to eat, his meal was no longer the tasty dinner she intended for him. But he was stoic about it. "I'm not one for "dining". I'm just "refueling", he'd often say.

Thursday was his "day off', when he could tinker with his car or work in the yard, planting yews, or building the stone wall that lined the driveway down where the barn had been. But often that too was honored in the breach. If an emergency case rang the office bell, or a phone call summoned him to a car accident, or to deal with an arm caught in a hay baler, the yard tools were dropped and the medical bag grabbed and off he would go.

Sundays were about the same. The family could go to St. John's for church, but most often he stayed home catching sleep after late night house calls, or taking care of a suddenly sick patient who just had to see the Doc that Sunday morning. Paul's grandfather was the Rev. Dr. Jacob Clutz, a Lutheran minister and professor at the Seminary in Gettysburg. So Paul felt some obligation to attend church when his practice permitted. On one such rare Sunday morning he came up to the church after our family was already seated in the pew, enjoying Janice Steiger's marvelous organ preludes before the service started. When he entered, usher Clarence Branthaver looked at him in surprise. "Who called you, Doc?!" Seems like a congregant had passed out and was on lying on the bench at the back of the church. Instead of joining his family in their pew, Paul immediately went to attend to sick person. But Clarence could hardly believe Doc had actually come to church just for the Sunday service!

Doc really enjoyed the time with his patients when they had a chance to swap stories with him, and he had the chance to joke with them and get kidded in return. He had no time to go to the clubs where he was a member, like the VFW or American Legion, just to have a beer and shoot the bull with the boys, like a lot of the men of the town enjoyed. But his conversations and interaction with his patients- his friends- were to him a far better substitute.

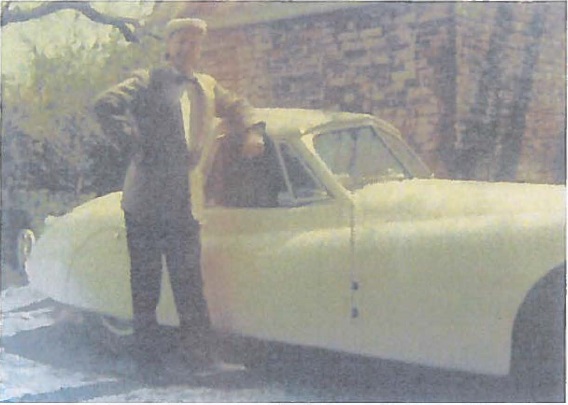

He loved sports cars. He loved sport car races. Road & Track was a favorite magazine. Driving fast on the back roads to make a house call was not well suited for his DeSoto sedan. He needed a car that could handle narrow mountain roads nimbly and fast, and safely.

So it was a happy day when he found a used 1952 Jaguar XK-120 for sale at a Chambersburg used car lot. After some haggling, he drove home his prize. That car was perfect for his high speed emergency calls over into the Little Cove, or out into The Comer, or getting a patient to the Chambersburg Hospital in an emergency before the town had its ambulance service. The little cream-colored convertible was recognized by the State Police. "There goes Doc Clutz", they'd say as the little Jag roared up Route 30, and let him go unhindered. Soon he found a Jaguar sedan for sale, and bought it for the family. In due course of time, the XK-120 was sold, to one of his patients who painted it black, but otherwise preserved it fully. I believe he still has it in his collection of classic cars. Paul went on to a succession of sports cars - an AMX that would go like a scalded cat, a Porsche Carrera that stuck to the curves of the back road like glue at high speed. All well suited to his back roads visits to help a sick patient.

So it was a happy day when he found a used 1952 Jaguar XK-120 for sale at a Chambersburg used car lot. After some haggling, he drove home his prize. That car was perfect for his high speed emergency calls over into the Little Cove, or out into The Comer, or getting a patient to the Chambersburg Hospital in an emergency before the town had its ambulance service. The little cream-colored convertible was recognized by the State Police. "There goes Doc Clutz", they'd say as the little Jag roared up Route 30, and let him go unhindered. Soon he found a Jaguar sedan for sale, and bought it for the family. In due course of time, the XK-120 was sold, to one of his patients who painted it black, but otherwise preserved it fully. I believe he still has it in his collection of classic cars. Paul went on to a succession of sports cars - an AMX that would go like a scalded cat, a Porsche Carrera that stuck to the curves of the back road like glue at high speed. All well suited to his back roads visits to help a sick patient.

Change came to Mercersburg slowly after the war, but by the mid-sixties it seemed everyone in the surrounding countryside had a car, and instead of driving a few miles into Mercersburg to shop, they went to Chambersburg or Hagerstown to the shopping centers and big stores with the low prices and big variety. The small shops in Mercersburg slowly closed up. The same trend changed Doc Clutz's practice. The fire department now had an ambulance, and emergency cases went directly to the hospital. Most babies were now delivered in the hospital, not at home. He rarely had need to stitch up a wound other than a minor cut, and had few occasions to set a broken bone after x-raying the patient. His practice had becoming largely limited to internal medicine. But that probably was a good thing. He and Cotty were now in their early sixties. They had rarely taken any kind of vacation, due to the constant demands of the practice. The boys were all living away, with their own lives to lead. Their widowed mothers passed away in the early/mid 1960's, which ended the Sunday trips of "the International Trade" to Gettysburg. So Paul and Cotty finally had time to take that long-awaited trip across the country. He loved to drive, and so did she. So they could share the driving. He loved his photography, and found plenty of photogenic scenery and architectural treasures to fill up rolls of 35 millimeter color slide film as they explored America together.

By the mid 1970's, their traveling was more aimed at visiting Henry's family in Texas, David's in upstate New York, and Bill in New York City. For years, Henry had devoted his vacation to an annual trip back to Mercersburg for his children to spend time with their grandparents, and to get to know the town, and the people, that had helped form his early years. David and his family made their visits on holidays and the occasional weekend. Bill would take the train to Harrisburg and Paul would drive up to meet him there and bring him home. So despite the distances, Paul and Cotty were able to enjoy the close family relationships they treasured.

Doc began to cut back his practice, taking no new patients, content to serve those who by now were old friends as well as patients. After all, he had practiced in town for 40 years, and was nearly 70. He'd earned the right to have a bit more time to himself, and time to finally share companionship with Cotty. She of course was delighted. The phone rang less, the constant threat of demands for Doc in the middle of the night w as over. But he still did rise in the night when summoned to the country.

On one occasion he arrived at the farmhouse to find the patient, a rather stout woman, had fallen out of her bed and couldn't get up. He lifted her up with difficulty, but got her back into bed. A day later he realized his new discomfort was a hernia, incurred by the strain of that effort. He had it surgically repaired, but now in his late sixties, realized he had to end such work.

After retirement in 1983, Paul and Cotty would often drive to Gettysburg on a Sunday afternoon. No more "international trade" visits, but just a pleasurable drive around the Battlefield. He took a photo of every monument on the Battlefield before he was done, and Cotty put them into albums. Sadly, these treasures have been lost. They also took similar trips into the countryside in every direction from Mercersburg. Again he took photos, not of monuments, but of barns, interesting landscape features, and just whatever struck his fancy. Cotty put those into albums, and fortunately they are still in the family for us to enjoy his artistic compositions.

Catherine developed cardiac problems, and soon Paul's trips to the Chambersburg Hospital were not to see a patient, but to visit his wife in the Cardiac Care Unit. A young cardiologist prescribed strong medication to control her arrhythmia- too strong - and too busy to follow up to see if it was. So Paul, now retired from practice but not retired from his concern for Cotty, took it upon himself to adjust the medication. The lower dose reduced the debilitating side effects while still controlling the arrhythmia. They were able to go about their lives in somewhat more normal fashion. They could continue going for drives in the countryside. They could go back to enjoying the home cooking at the Foot of The Mountain, where they could also enjoy the camaraderie of the usual regulars, folks they'd known for so many years.

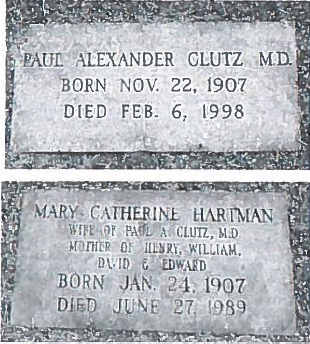

Eventually, the stairs of the house became too much for Cotty, so Paul moved her bed down to the office, with its warm radiant heated floor. On the night of June 26, 1989, (coincidently her grandson Daniel Paul's 19th birthday), she went into the office and went to sleep. Paul still slept in his upstairs back bedroom. Next morning he came downstairs to shave as he always had, trying to be quiet and not disturb the sleeping Cotty. When her caregiver arrived and went to her bedside, she called to Dr. Clutz. Cotty had passed away during the night. She now rests in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery, next to her infant son Paul Edward.

Paul remained in Mercersburg for the next three years. The Parkinson's disease that had been latent for many years, now emerged in full strength, stiffening his muscles, slowing his responses, affecting his memory. He still drove to the Foot of the Mountain, and walked up to the restaurant on the Square for his noon meals. But now he found himself uncertain of the direction of home when he left the restaurants. Several times he fell, walking to the Library, and unaware of what had happened. Fortunately his good neighbors were there to pick him up, dust him off, and get him home. Cotty's faithful friend and helper Bernice Lowans came regularly to the house, keeping it clean, seeing he had food, generally checking on her Dr. Clutz. But by early 1991 she could see it was no longer safe for him to be alone in that big house. She feared for him falling down the stairs with his knees now so stiff, and confided her concern to me.

I drove down to see him, and realized that just in the last month his physical condition had deteriorated, just as Bernice had said. Years before, Cotty had wanted them to sell the big house and move to the Lutheran retirement community in Gettysburg. Pop would have none of it. He liked his house, still went to his office every day, if only to read and putter around. And he loved Mercersburg. His friends were there. He once told me, "before you put me in one of those nursing homes, just shoot me!" So I was surprised and relieved when I suggested it was now time for him to leave the house and move to a comfortable assisted living residence, and he quickly agreed that it was indeed time. On the 20th of May, 1991, we drove to Binghamton to Woodland Manor, just blocks from my home, and he settled in.

A few months later Tom and Kitty Steiger stopped in to see him there on their way north. I am certain he was delighted to see them again. Next day when I stopped in to see him, he said nothing of their having been there. I found out about it some days later, not from him. His short term memory had deteriorated.  Just after his 85th birthday in November 1992, he transferred to the Susquehanna Nursing Home. It would be his home for the next five years. On February 6, 1998, age 90, he passed away. He now rests in the family plot in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery, beside Cotty and his infant son Paul Edward. In their later years they had been so interested in Civil War history, and now they will remain forever in the hallowed ground of that great battlefield. But a large part of his spirit will remain in the town he had come to love, the community to which he had given so much of his life, and which had given him so much joy - Mercersburg.

Just after his 85th birthday in November 1992, he transferred to the Susquehanna Nursing Home. It would be his home for the next five years. On February 6, 1998, age 90, he passed away. He now rests in the family plot in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery, beside Cotty and his infant son Paul Edward. In their later years they had been so interested in Civil War history, and now they will remain forever in the hallowed ground of that great battlefield. But a large part of his spirit will remain in the town he had come to love, the community to which he had given so much of his life, and which had given him so much joy - Mercersburg.

Author's note: My father was my model, my mentor, and my hero, in so many ways. My mother was my friend, my supporter in all that I put my hand at doing. I admit to both prejudice and pride in writing these memories of them and in what they accomplished in their lives. Every time I come to Mercersburg I am reminded of the love that the town - its wonderful people, especially his former patients - had for them. I know Mother and Pop would want me to express their thanks and gratitude for the .friendship, respect, and assistance they had been given by the good people of the community that had become their home, 1933-1991. - David Clutz, Nov. 2016

Back to Persons of Interest, Mercersburg Area, WW II